Galaxy-surveying spacecraft Gaia detects two new planets

TAU researchers lead study that identifies previously unknown worlds

Support this researchResearchers from Tel Aviv University (TAU) led the discovery of two new planets in remote solar systems by the European Space Agency’s (ESA) spacecraft Gaia, a star-surveying satellite on a mission to chart a 3D map of our Milky Way galaxy and beyond. Because this is the first time that Gaia has successfully located new planets, the planets were given the names Gaia-1b and Gaia-2b.

The research was led by Professor Shay Zucker, Head of TAU’s Porter School of the Environment and Earth Sciences, and doctoral student Aviad Panhi of TAU’s Raymond and Beverly Sackler School of Physics & Astronomy. The findings were presented in a study conducted in cooperation with the ESA and the research groups of the Gaia space telescope, and were published on May 19 in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

There are eight planets in our solar system, but there are hundreds of thousands of other planets in our galaxy, the Milky Way, which contains untold numbers of solar systems. Planets in remote solar systems were first discovered in 1995 and have been an ongoing subject of astronomers’ research ever since, in hopes of using them to learn more about our own solar system.

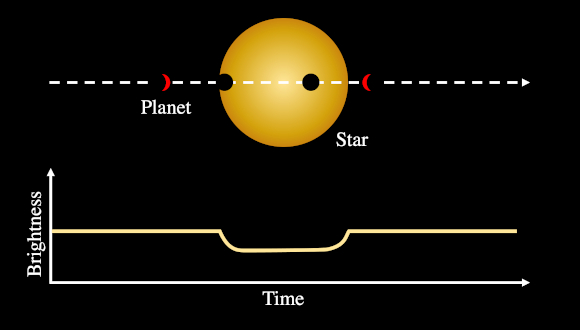

“The planets were discovered thanks to the fact that they partially hide their suns every time they complete an orbit, causing a cyclical drop in the intensity of the light reaching us from that distant sun,” Panhi explains. “To confirm that they are in fact planets, we performed tracking measurements with the American telescope called the Large Binocular Telescope, located in Arizona. This telescope is equipped with two giant mirrors, each with a diameter of 8.4 meters, making it one of the largest telescopes in the world today. This telescope makes it possible to track small fluctuations in a star’s movement which are caused by the presence of an orbiting planet.”

To fulfill its mission, Gaia scans the sky while rotating around an axis, tracking the locations of about 2 billion suns in our galaxy with precision of up to a millionth of a degree. While tracking the suns’ locations, Gaia also measures their brightness — an incomparably important feature in observational astronomy, since it can indicate a lot about the physical characteristics of celestial bodies. Changes documented in the brightness of the two remote suns were what led to the discovery.

Professor Zucker has extensive experience in discovering planets, dating back to his days as a student of senior TAU astronomer Professor Tzevi Mazeh. “The measurements we made with the telescope in the U.S. confirmed that these were in fact two giant planets, similar in size to the planet Jupiter in our solar system, and located so close to their suns that they complete an orbit in less than four days, meaning that each Earth year is comparable to 90 years of that planet,” Professor Zucker says. “The discovery of the two new planets was made in the wake of precise searches, using methods of artificial intelligence. We have also published 40 more candidates detected by Gaia. The astronomical community will now have to try to corroborate their planetary nature, as we did for the first two candidates. The data continues to accumulate, and it is very likely that Gaia will discover many more planets with this method in the future.”

This discovery marks another milestone in the scientific contribution of the Gaia spacecraft’s mission, which has already been credited with a revolution in the world of astronomy. Gaia’s ability to discover planets via the partial occultation method, which generally requires continuous monitoring over a long period of time, has been doubted up to now. The research team charged with this mission developed an algorithm specially adapted to Gaia’s characteristics, and searched for years for these signals in the cumulative databases from the spaceship.

And what about the possibility of life on the surface of those remote new planets? “The new planets are very close to their suns, and therefore the temperature on them is extremely high, about 1,000 degrees Celsius, so there is zero chance of life developing there,” Panhi says. “In the astronomy community, such a planet is called ‘Hot Jupiter’ — ‘Jupiter’ because of its size, and ‘hot’ because of its proximity to its sun. Even though there is no real chance of life on the planets we found, I’m convinced that there are countless others that do have life on them, and it’s reasonable to assume that in the next few years we will discover signs of organic molecules in the atmospheres of remote planets. Most likely we will not get to visit those distant worlds any time soon, but we’re just starting the journey, and it’s very exciting to be part of the search.”