TAU researchers use plant remains to reconstruct climate change in ice-age era Middle East

Study also sheds light on transition from nomadic to settled societies

Support this researchBased on the identification of plant remains, Tel Aviv University (TAU) and Tel-Hai College researchers have reconstructed in detail the climate in the Land of Israel at the end of the last ice age, 10,000-20,000 years ago. The researchers claim that significant climate changes characterizing the period, manifested by sharp differences in temperature and precipitation not only seasonally but throughout the year, were a significant influence in the transition from a nomadic hunter-gatherer society to permanent settlement and an agricultural way of life.

The study also provides the first information pertaining to the history of the region’s flora and its response to past climate change. Against the backdrop of the Glasgow climate conference, the researchers say that understanding the response of the region’s flora to dramatic climate changes in the past can help to preserve the regional variety of plant species and plan for current and future climate challenges.

The research was conducted by Dr. Dafna Langgut of the TAU’s Department of Archaeology and Steinhardt Museum of Natural History; Professor Gonen Sharon, Head of the MA Program in Galilee Studies at Tel-Hai College; and Dr. Rachid Cheddadi, an expert in evolution and palaeoecology at the University of Montpellier, Institute of Evolutionary Sciences (ISEM) Montpellier, France. The groundbreaking study was recently published in the leading scientific journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

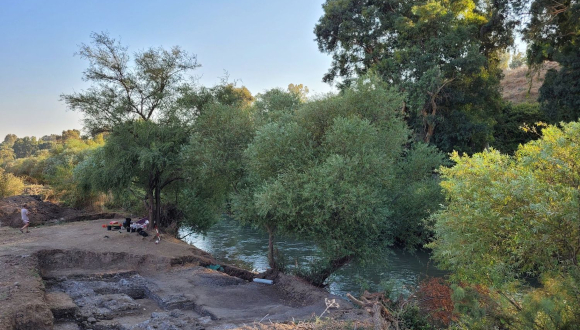

The study was conducted at the prehistoric archaeological site Jordan River Dureijat (“Jordan River Stairs”) on the shores of the Paleo Lake Hula. The site is unique for its exceptional preservation conditions, yielding finds that enabled discovery of fishing as the primary activity of its early local residents. Preserved botanic remains preserved also enabled researchers to identify the plants that grew 10,000–20,000 years ago in the Hula Valley and its surroundings.

This period saw the transition from a nomadic to a settled lifestyle that occurs during a period of dramatic climate change. “In the study of prehistory, this period is called the Epipalaeolithic period,” Professor Sharon, supervisor of the Madregot Hayarden excavation, explains. “At its outset, people were organized in small groups of hunter-gatherers who roamed the area. Then, about 15,000 years ago, we are witness to a significant change in lifestyle: the appearance of settled life in villages, and additional dramatic processes that reach their apex during the Neolithic period that followed. This is the time when the most dramatic change of human history occurred – the transition to the agricultural way of life that shaped the world as we know it today.”

Dr. Langgut, an archaeobotanist specializing in identification of plant remains, elaborates on the other major characteristic of this period, the climatic changes that occurred in the region. “Although at the peak of the last ice age, about 20,000 years ago, the Mediterranean Levant was not covered with an ice sheet as in other parts of the world, the climatic conditions that existed nevertheless differed from those of today,” Dr. Langgut says. “Their exact characteristics were unclear until this study. The climatic model that we built is based on reconstruction of the fluctuation of the spread of plant species, indicating that the main climatic change in our area was expressed by a drop in temperature (up to five degrees Celsius less than today), whereas the precipitation amounts were close to those of today, only about 50 mm less than today’s annual average.”

About 5,000 years later, however, in the Epipalaeolithic period (about 15,000 years ago), a significant improvement in climate conditions can be seen in the model, Dr. Langgut continues. An increased prevalence of heat-tolerant tree species, such as olive, common oak, and Pistacia, indicate an increase in temperature and precipitation. During this period, the first sites of the Natufian culture appear in the region. It could very well be that the temperate climate assisted in the development and flourishing of this culture, in which permanent settlement, stone structures, food storage facilities, and more first appear on the global stage.

The next stage of the study deals with the end of the Epipalaeolithic period, about 11,000-12,000 years ago, known globally as the Younger Dryas period. This period is characterized by a return to a cold, dry climate like that of the ice age, causing somewhat of a climate crisis around the world. The researchers claim that until this study, it was unclear whether and to what extent there was any evidence of this period in the Levantine region.

“The findings that arise from the climate model presented in the article show that the period was characterized by climatic instability, intense fluctuations, and a considerable drop in temperatures,” the researchers say. “Nevertheless, while reconstructing the precipitation, a surprising phenomenon was discovered: the average quantities of rainfall reconstructed were only slightly less than those of today; however, the precipitation was distributed over the entire year, including summer rains.”

The researchers claim that such distribution assisted in the expansion and thriving of annual and leafy plant species. The gatherers who lived in this period now had a wide, readily available variety of gatherable plants throughout the entire year. This variety enabled their familiarity just before domestication. The researchers are of the opinion that these findings contribute to a new understanding of the environmental changes that took place on the eve of the transition to agriculture and domestication of animals.

“This study contributes not only to understanding the environmental background for momentous processes in human history such as the first permanent settlement and the transition to agriculture, but also provides information on the history of the region’s flora and its response to past climatic changes,” Dr. Langgut concludes. “There is no doubt that this knowledge can assist in preserving species variety and in meeting current and future climate challenges.”