TAU astronomers identify star that survived encounter with a black hole

Discovery upends accepted view of encounters between stars and black holes

Support this researchAn international group of researchers led by Tel Aviv University (TAU) astronomers observed a flare caused when a star falls onto a black hole and is destroyed. But, surprisingly, this flare occurred about two years after a nearly identical flare named AT 2022dbl appeared at exactly the same location.

This is the first confirmed case of a star that survived an encounter with a supermassive black hole and came back for more. This discovery upends conventional wisdom about such disruption events and suggests that these spectacular flares may be just the opening act in a longer, more complex story.

The study was led by Dr. Lydia Makrygianni, a former TAU postdoc and currently a researcher at Lancaster University in the UK, under the supervision of Professor Iair Arcavi, a member of the Department of Astrophysics at TAU’s School of Physics & Astronomy and the Director of the University’s Wise Observatory in Mizpe Ramon. The results are published in the July 1, 2025, issue of the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

At the center of every large galaxy lies a black hole that is millions to billions of times the mass of the sun. Such a supermassive black hole exists also in our own Milky Way Galaxy, and its discovery was awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in physics. But it’s not well understood how such monsters form, nor how they affect their host galaxies.

One of the main challenges in understanding these black holes is that they are invisible. A black hole is a region of space where gravity is so strong that not even light can escape. The supermassive black hole in the center of the Milky Way was discovered thanks to the movement of stars in its vicinity. But in other, more distant, galaxies, such movement cannot be discerned.

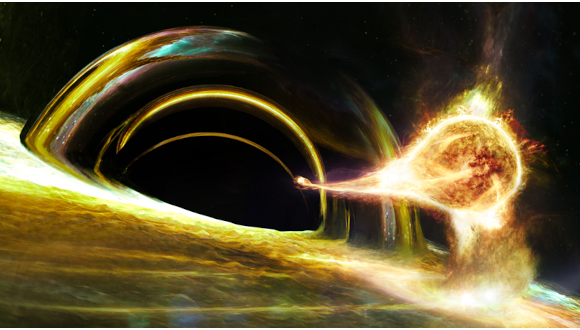

Once every 10,000 to 100,000 years, a star will wander too close to the supermassive black hole in the center of its galaxy, resulting in it getting ripped to shreds. Half of the star will be “swallowed” by the black hole, and half thrown outward. When material falls onto a black hole, it does so in a circular fashion, much like water going down the bathtub drain. Around black holes, however, as the velocity of the rotating material approaches the speed of light, the material is heated and radiates brilliantly. Such an unlucky star thus “illuminates” the black hole for a few weeks to months, providing astronomers with a brief opportunity to study its properties.

The TAU researchers say that these flares have not been behaving as expected. Their brilliance and temperature were much lower than predicted. After about a decade of trying to understand why, AT 2022dbl may have provided the answer.

The repetition of the first flare in an almost identical manner two years later implies that at least the first flare was the result of a partial disruption of the star, with much of it surviving and coming back for a nearly identical additional passage. These flares are thus more of a “snack” by the supermassive black hole than a “meal.”

“The question now is whether we’ll see a third flare after two more years, in early 2026,” says Professor Arcavi. “If we see a third flare, it means that the second one was also a partial disruption of the star. So maybe all such flares, which we have been trying to understand for a decade now as full stellar disruptions, are not what we thought.”

If a third flare does not occur, then the second flare could have been the full disruption of the star. The implication is that partial and full disruptions look almost identical, a prediction made before this discovery by a research group led by the Hebrew University’s Professor Tsvi Piran. “Either way,” says Professor Arcavi, “we’ll have to re-write our interpretation of these flares and what they can teach us about the monsters lying in the centers of galaxies.”

Professor Ehud Nakar, Chair of TAU’s Department of Astrophysics, and students Sara Faris and Yael Dgany of Professor Arcavi’s research group also took part in the research, alongside many international collaborators.