TAU researchers discover mechanism that allows melanoma cancer cells to paralyze immune cells

Finding has far-reaching implications for treating deadly skin cancer

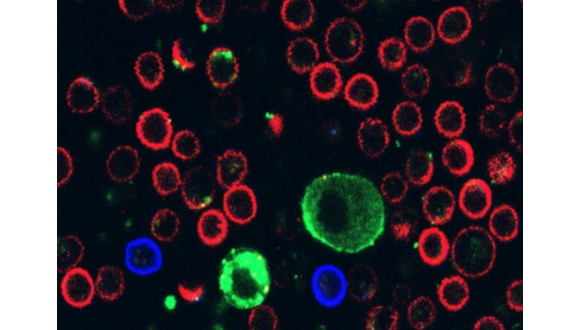

Support this researchA new international study led by the Gray Faculty of Medical & Health Sciences at Tel Aviv University (TAU) finds that melanoma cancer cells paralyze immune cells by secreting extracellular vesicles (EVs), tiny, bubble-shaped containers secreted from a given cell. Cancer cells essentially fire these vesicles at the immune cells that attack it, disrupting their activity and even killing them. The research team believes that this discovery has far-reaching implications for possible treatments for the deadliest form of skin cancer.

This dramatic breakthrough was led by Professor Carmit Levy of the Department of Human Genetics and Biochemistry at TAU’s Gray Faculty, in collaboration with research teams from Sheba Medical Center, the Weizmann Institute of Science, the University of Liège, the Technion, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Wolfson Medical Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Hadassah Medical Center, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Rabin Medical Center, Paris-Saclay University, and the University of Zurich. The study’s findings were published on December 15, 2025, in the journal Cell.

Professor Levy explains her research in the YouTube video below:

Melanoma is the deadliest type of skin tumor. In the first stage of the disease, melanocytic cells divide uncontrollably in the skin’s outer layer, the epidermis. In the second stage, the cancer cells invade the inner dermis layer and metastasize through the lymphatic and blood systems.

In previous studies, Professor Levy discovered that as melanoma cells grow in the epidermis, they secrete large vesicles called melanosomes, which penetrate blood vessels and dermal cells, forming a favorable niche for the cancer cells to spread.

“We began studying these vesicles,” Professor Levy explains. “I noticed that on the vesicles membrane there was a ligand — a molecule that is supposed to bind to a receptor found only on immune cells called lymphocytes, specifically on lymphocytes that can kill cancer cells when coming into direct contact with them. I then hypothesized that this ligand latches onto lymphocytes that come to kill the melanoma.

“This was an innovative and odd idea and we started investigating it in the lab. When we got more and more evidence that this idea is correct, I spoke with colleagues around the world, and invited them to join and contribute their expertise: from Harvard, from Sheba and from Ichilov’s pathology department, from the Weizmann Institute, from Zurich, Belgium and from Paris — all came together in a joint effort to decipher the cancer’s behavior.

“And the achievement is enormous: we discovered that the cancer essentially fires these vesicles at the immune cells that attack it, disrupting their activity and even killing them.”

Professor Levy emphasizes that the discovery is promising, but more work is required in order to translate it into a new therapy. “We still have a great deal of work ahead of us, but it is already clear that this discovery can have far-reaching therapeutic implications,” she says. “It will enable us to strengthen immune cells so they can withstand the melanoma’s counterattack. In parallel, we can block the molecules that enables vesicles to cling to immune cells, thereby exposing the cancer cells and making them more vulnerable. Either way, this study opens a new door to effective immunotherapeutic intervention.”